I Completed The David Goggins Challenge And Asked My Garmin How I Did

David Goggins is an interesting personality. From my perspective, he’s one of those figures you either love or hate. I’m impressed by his perseverance and drive, but his life and fitness philosophy don’t appeal to me much. I guess my attitude resonates more with “zen-like” runners, such as Anton Krupicka, Scott Jurek, or Eliud Kipchoge. Goggins’ bestseller, “Can’t Hurt Me,” sits on my library shelf, but the bookmark is stuck somewhere in the middle. Sadly, I have no intention of advancing in the lecture.

Still, the idea of completing the infamous David Goggins challenge has always appealed to me. Despite my lukewarm approach toward its inventor, the challenge offers a unique way to try oneself in a different running “dimension.” The challenge is simple: run 4 miles (6.5 kilometers) every 4 hours, across 48 hours. This means going for a run, resting for about three hours (the four-hour difference is counted between the start of each run), rinse, and repeat. No matter the time of day or weather. Fun fact: when you do the math, the challenge is the equivalent of running almost two marathons within two days.

I’ve been toying with the idea of completing the David Goggins challenge for several months now. Finally, November 2023 gave me a great opportunity to take it up. The preceding month, October, was pretty hectic. I finished the Berlin marathon (you can read my running report here) and climbed Kilimanjaro a week later. In late November, I was well-rested and eager for a new challenge – something grandiose yet doable. Ideally something I could take up just a stone’s throw from my apartment. Perfect time for the David Goggins Challenge.

Preparation

Over the years, I’ve learned that preparations for any type of physical challenge are important. Equally crucial, however, is keeping it simple and concise. So, I spent one afternoon writing down the plan and getting myself ready:

- Conducted short research on Reddit to learn how others approached the challenge.

- Allocated 48 hours solely for David’s challenge, daily chores, and rest while watching two series simultaneously: “Jazz” by Ken Burns and HBO’s “Rome” (rewatching it after more than a decade; still stands out as one of my favorite series ever).

- Bought snacks, fruits, and, most importantly, ingredients to prepare eight large servings of spaghetti carbonara—my favorite running food. Full of carbs and protein, easy to prepare and digest.

- Wrote down my schedule in Notion and set up a series of alarms on my Garmin accordingly.

- Moved to a separate room, sparing my fiancée the burden of being woken up twice every night for two consecutive days.

- Prepared three sets of running clothes in advance, including a waterproof Goretex jacket, a headlamp for night runs, headphones, etc. It’s crucial, especially at night, not to waste time looking for fresh clothes (as it deduces minutes from the sleep time).

The Challenge: The Subjective

Contrary to what I read before completing the challenge, it is not as hardcore as Goggins himself. The runs themselves are not physically brutal. I think that 4 miles is a very forgiving distance, even when completed repeatedly, a dozen times. I may have had the advantage of always making sure that I got at least some sleep at night, as well as taking care of nutrition (hail carbonara!). Quite honestly, the most difficult part was waking up at night, getting dressed, and jogging into the darkness. This was especially problematic during the second night of the challenge. Running at night, soaking wet, through the empty park made me truly appreciate the day runs. The first 8:00 am run in the sun after three days of running in the dark was glorious.

In hindsight, one thing that I should have done is stretch more. As I mentioned before, the physical load your body has to bear is equivalent to two marathons. My constantly stiff (yet not painful) legs were begging for a stretching and rolling session. Also, at the end of the last few runs, my back and shoulders got super stiff and started to hurt a bit. But I was too busy eating or doing daily chores to properly take care of my muscles (David Goggins: were you too busy, or are you making up excuses, boy? Me: you’re probably right, David, I am a mere slave trapped in the cage made of excuses).

The Challenge: The Objective

After completing the challenge, I was super eager to pull the data from my Garmin and see what the data reveals about my runs. Surprisingly, this is not a trivial task. Initially, I thought that every workout tracked by Garmin was being saved locally on my watch, but this is so not true! To retrieve your data as files, you need to first sync your device and send the data to Garmin servers through Garmin Express. Only then, using Garmin Connect, can you download a .csv data summary of your workouts from the website - but this data is super limited!

Contrary to what you might expect, the workouts cannot be fully pulled locally from the watch. Well, you know how the saying goes: “not your key, not your coin”; I’d say “yes, your watch, but no, not your data.” To get your hands on your `.fit` workout files, you need to explicitly ask Garmin to share them with you. This takes a few hours up to a few days until you receive an email message from the company with the link to your data. Only then, using some open-source libraries such as fitdecode or fitparse, may you attempt to parse out the data that interests you and start gaining some insight from it. I built a small script that takes a set of .fit files from my running workouts and converts them into a human-readable dataframe.

Note: In theory, .fit files should be exhaustive and contain all the information that your Garmin watch has access to. Sadly, I couldn’t find some crucial information such as the number of calories burned, training load, or dehydration level. I know that Garmin does store them somewhere since I can find them (and many, many more items) in my Garmin Connect mobile app dashboards. Nevertheless, I managed to pull out crucial data about my run and inspect it using this simple notebook.

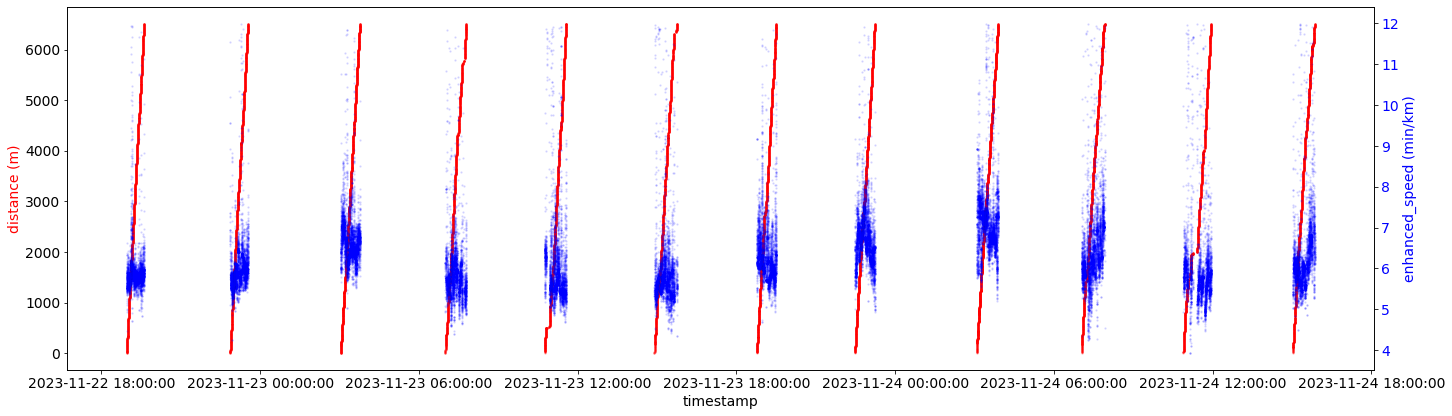

Each of the twelfth inclined red lines represents a distance of 4 miles (6.5 km). Between the start of each run, there are 4-hour gaps. As demonstrated by the chart, my first run started on 11/22/23 at 19:00, and the challenge was finished with the final run at 16:00 on 11/24/23. To compute the average pace, I converted the speed from default units (meters per second) to runner-readable pace (minutes per kilometer). It turns out that my pace was not steady at all, as it would be if I were running a marathon, for example. I was having fun: going faster when I felt like it or slowing down. This amounted to an average pace of around 6 min/km, indicating that every 4-mile run took me around 40 minutes.

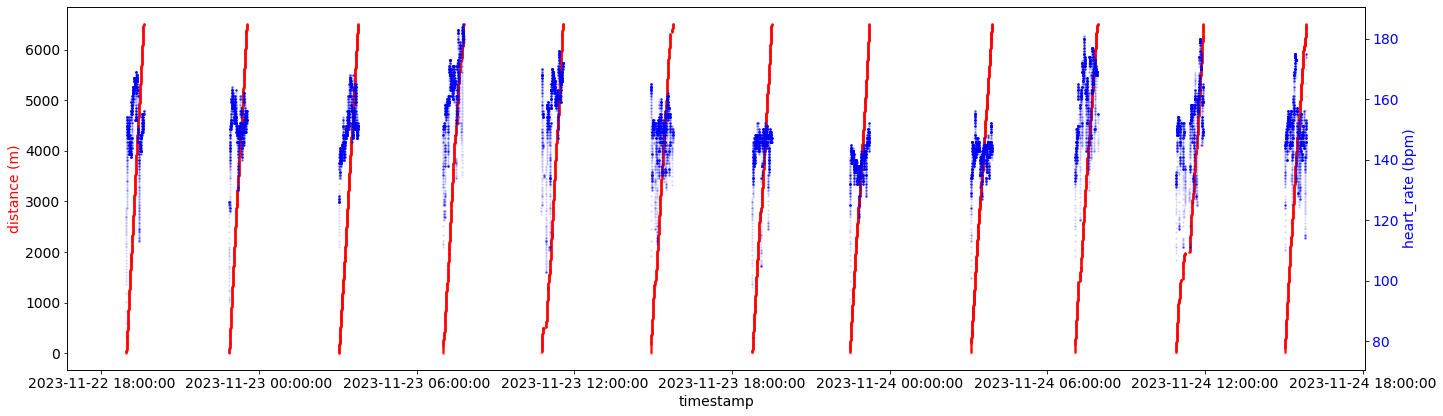

The heart rate also reflects the fact that I was running “by feeling.” The data shows that during the challenge, my minimal heart rate was 76 bpm, my average heart rate was 150 bpm, and my max heart rate was 180 bpm. These are very plausible and non-surprising numbers. An interesting fact: the further in I am in the challenge, the bigger the variance in speed/heart rate. It clearly shows that I was much more fatigued, unfocused, and rather dragging my body than running in a composed manner.

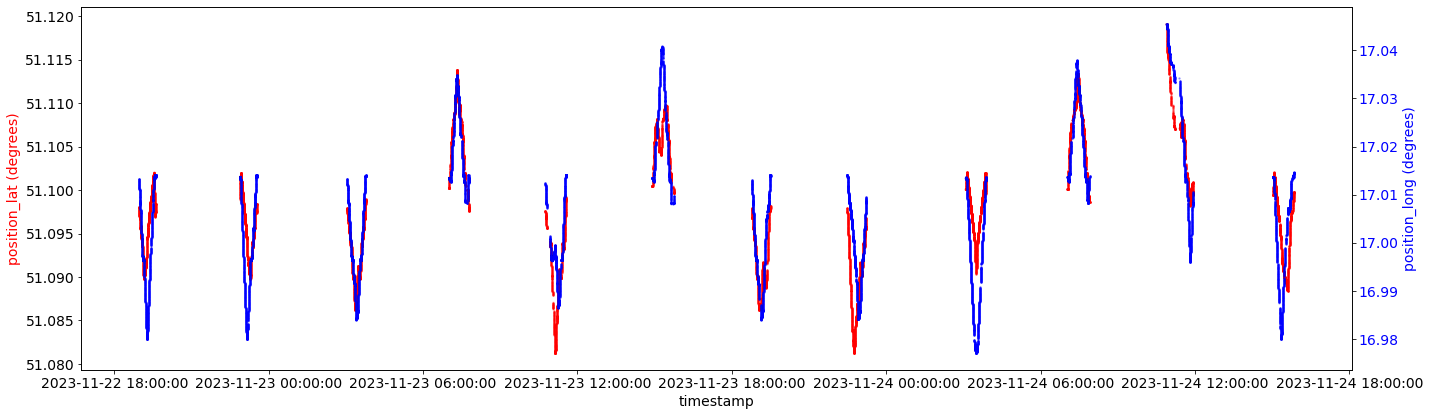

Another piece of data being saved is the latitude and longitude information from the built-in GPS. Funny enough, by default, Garmin saves latitude and longitude in the obscure “semicircle” units. Not sure what the use case for this representation is, so converted semicircles to degrees. So now, it is clear that I was located roughly at 51°N 17°E at the time of the run (which you can check by looking those coordinates up).

That’s all the valuable information that I was able to get from my Garmin .fit files for this challenge. I managed to pull information about the running cadence or running power, but that’s not really interesting. It’s a shame; we know for a fact that Garmin collects tons and tons of items, even most exotic data, like estimated sweat loss.

In summary, completing the David Goggins Challenge provided a unique and demanding experience. The subjective aspects highlighted physical challenges, especially during nighttime runs, while the objective (sparse) data from my Garmin revealed insights about my pace or heart rate. The overall experience was enlightening and rewarding, showcasing the intersection of physical and mental endurance.