Bayesian thinking- What can we learn about reasoning from the machines?

Bayes’ rule may be one of the numerous formulas students are introduced to during A-Level maths course. I believe that most pupils (including myself back in the days) usually learn it by heart, use it without thought during their statistics exam and quickly forget it. But Bayesian reasoning may actually be one of the most important mathematical tools we could apply in real life. It is a powerful means to test and enhance our thinking so that we can overcome common fallacies of reasoning.

The number game- a simple thought experiment

An elegant and simple introduction to Bayesian thinking is known as a number game (based on the thesis by Josh Tenenbaum). Let’s say I have a big bag of numbered balls (for simplicity, the numbers are integers from 1 to 100). The first question I want you to answer is:

If I take few balls randomly out the bag, what would be the most likely number to come up?

Well, you don’t know much about my bag. When I am about to pick a random ball, you are unable to say whether number 66 is more likely to be drawn than number 13. This means that probabilities of picking any number in the known range are the same.

Now, let me pick one random ball from the bag. There it is, number 16. Now, knowing that this number was in my bag, tell me which number is most likely to be selected next.

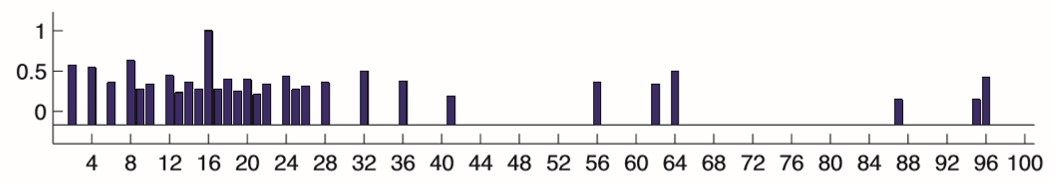

Now, we have some new data which we can take into consideration. Since we know that 16 was present in our bag of numbers, we are may start reasoning, that we are more likely to expect 6 (since 16 and 6 have a common digit) or 17 (since it lies on a number line just next to 16) then say, 99. The actual results of this experiment are presented in the figure below.

Now, let’s choose four numbers. There they are- 16, 8, 2 and 64. Now, given theose numbers, what would be the most likely number to come up next?

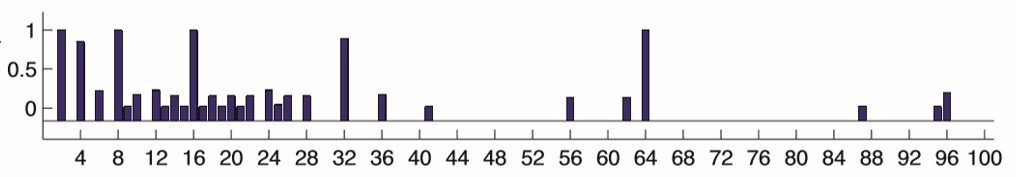

Now we get even more numbers. We may try to take advantage of the new data and match those values to some pattern or a rule. Which rule governs our set of numbers? Well, all numbers chosen are even. Should we expect an even number then? All numbers are also powers of 2! So maybe 32 would fit our prediction nicely? The following figure shows that those are all very good candidates for a prediction.

Last example. The selected numbers are 16, 23, 19 and 20. What’s coming up next?

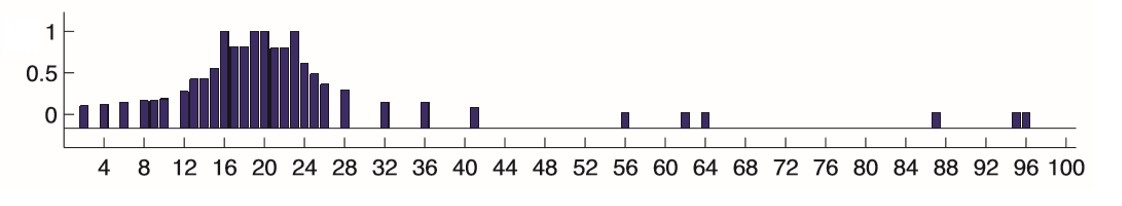

Now the reasonable answer would be 17, 22 or 21, because the new data indicates that numbers in the bag have values close to to 20. The other possible predictions are as shown in the chart.

In every scenario I have presented, we follow the same reasoning. Firstly, we have some the initial knowledge (we pick randomly from the set of integers from 1 to 100). Secondly, we are given some new data, which improves our current state of knowledge and can help us to make a correct guess.

The baffling mathematics of drunk driving

Having vague understanding of the Bayes’ theorem, we may use an example to illustrate how this rule can be applied in real-life. Imagine you pick up your girlfriend from a party in your car. While you are returning home you get pulled over by the police. The officer suspects that you have been drinking. Your car indeed smells like alcohol and cigarettes plus you look tired, so it is no surprise that you are asked to take a breathalyser test. Sadly, although you know you haven’t had a sip of beer, the test indicates that you are drunk. How can you deal with this startling situation? This is where the Bayes’ theorem comes in handy.

Let’s introduce some mathematical notation. We have an event D, which indicates if you are drunk or not. D=1 means that you have been drinking while D=0 indicates sobriety. An event B shows the result of the breathalyser test. B=1 means that the device says that you have been drinking. B=0 means that you have been identified as a sober driver. Simple right? Now let’s investigate some basic probabilities:

- Assume that the breathalyser test always detects a drunk person i.e. B=1 given D=1 is always 100%. This can be written as \(P(B=1 \mid{D=1})=100\%\).

- Breathalysers are smart devices, but they are not perfect. It may happen (as it did in your case), with a probability of 5%, that somebody is identified as drunk while being actually sober. This means that \(P(B=1 \mid{D=0})=5\%\).

In our current situation, we would like to know the answer to the following question:

What is the overall probability of that a driver has not been drinking, given that the breathalyser indicates otherwise?

The mathematical formulation of the question can be expressed as finding the probability P(D=0|B=1). The first answer that comes to mind is obviously 5%, right? I have just said, that there is 5% chance of the test being wrong. Well, let’s take advantage of the Bayes’ theorem to clarify this conundrum.

\[P( D=0 | B=1) = \frac{P(B=1|D=0)P(D=0)}{P(B=1)}\]To solve our problem we need to evaluate two values P(D=0) and P(B=1). While P(B=1) can be easily calculated, the most important element of the equation is the term P(D=0).

P(D=0) is known as a base value (or prior). It is a statistical piece of data, which helps us to get the full insight to evaluate the problem. By analogy to our number game, the base value was given by the numbers we have seen before guessing the number of a next ball. In our new example, the base value is the probability that a driver is not drunk, this is what P(D=0) stands for. For sake of our example we may say that, on average, 1 person out of 1000 people drives under influence of the alcohol, i.e. P(D=0)=999/1000.

The probability of test being positive P(B=1), is the sum of two factors:

- Test was positive and the driver was drunk, P(B=1,D=1)

- Test was positive and the driver was sober, P(B=1,D=0)

Now using Bayes’ theorem and product rule for the denominator we may solve our equation.

\[P( D=0 | B=1) = \frac{P(B=1|D=0)P(D=0)}{P(B=1,D=0)+P(B=1,D=1)}\] \[P( D=0 | B=1) = \frac{5\cdot 0.999}{5\cdot 0.999+ 100\cdot 0.001}=0.98\]This means that there is 98% chance that the driver is sober, given that the test indicates otherwise! Suprising, isn’t it? When we think about it for a while, it actually does make sense. There are so few people who are drunk driving, that a policeman must be aware of the fact, that most drivers who are pulled over and get identified as drunk, are most likely sober. But what if we happen to be pulled over by an officer who is not aware of that fact? The solution is straightforward. Ask the policeman to redo the test and simply breath into a second device. Mathematically it is equivalent to redoing our calculations. The only difference is, we use our old solution as a new base value. The new prior is richer in information and will deliver a better reflection of the reality. The new probability equals 71% and will continue to decrease with every new test. So the conclusion is: if you are sure that you are sober and the breathalyser indicates otherwise, ask for as many test as you possibly can and you are bound to be all right. That is a suprising and very neat mathematical lesson we could apply in real-life situation. Now, let’s add some psychology to our story…

The Bias’ theorem - how we pick our priors

We may take a closer look at the psychological view on the Bayes’ theorem. In his bestselling book Thinking, Fast and Slow , Daniel Kahneman describes an interesting problem. Let’s reverse roles by stepping into shoes of a police officer, whose task is to solve the following conundrum.

Last night there was a hit and run case reported. All the witnesses confirm unanimously, that a pedestrian was hit by a cab. There are two taxi companies in our city, Company Red and Company Blue. We have access to the following data:

- We know that 85% of all taxis in the city belong to the Company Red. The remaining 15% belongs to the Company Blue.

- We have identified a witness, who could clearly see the accident. The witness is sure that the Red taxi had caused the accident. The court has established that there is 80% probability that witness’ statement is true.

So what is the probability that the accident was actually caused by the Red taxi? Well, we have already seen what happens when we think only about the core of the problem and forget about the base value. The study conducted by Kahneman confirms our observation- it has shown, that people neglect the prior and their reasoning is guided usually by the data provided by the witness. The answer given by the participants was in most cases 80%. The base value tends to be neglected due to the fact, that our brains have hard time dealing with purely statistical data. What is easier to digest and quickly draws our attention, is the relationship between the cause and the effect. After all, what does the number of cabs in the city has to do with the fact that this specific taxi driver has caused the accident? Now we do know, that the sole fact, that we are 6 times more likely to encounter the Red taxi then the Blue taxi on the street, may imply, that we are 6 times more likely the be hit by the Red taxi then the Blue taxi. This purely statistical fact is rarely taken into consideration. In the end, the probability that the accident was caused by the red taxi is actually 41%, which is far from 80% declared by the participants. Interestingly enough the study has shown that when we rephrase the prior in the more emotional way, say:

Both companies have the same number of taxis, but Red taxis cause 85% of all taxi accidents.

people are more likely to reflect on the new prior, since now it makes the Red Company look bad, it conveys some intriguing, emotional message. This sentence makes us feel anxious about their drivers and we are very likely to remember this controversial piece of information and recall it e.g. during the trial. It satisfies our craving for the cause and the effect relationship, although it has identical mathematical meaning to our initial, vanilla prior.

What we can learn from the robots to refine our reasoning.

Bayes’ theorem is used widely in the field of artificial intelligence. There are numerous algorithms which base on this concept, such as Naive Bayes Classifier or Bayesian Networks. How a computer thinks is naturally very different from our reasoning. In the end, a human brain is one of the most astonishing gifts we have received from the nature. While being a superior to computers in many ways, it is very susceptible to prejudice, cognitive errors, erroneous generalizations and various mental shortcuts. That is why, when we are about to express our opinion or give a judgement, it may be helpful to step back, restrain our train of thought and question our state of knowledge. This can be done by taking advantage of hard, statistical facts to refine our reasoning. There are some more great examples in the short video by Julia Galef, which further demonstrate how to evaluate thought processes using the Bayesian legacy.