The best of GAN papers in the year 2018

This year I had a great pleasure to be involved in a research project, which required me to get familiar with a substantial number of publications from the domain of deep learning for computer vision. It allowed me to take a deep dive into the field and I was amazed by the progress done in the last 2-3 years. It is truly exciting and motivating how all different subfields such as image inpainting, adversarial examples, super-resolution or 3D reconstruction have greatly benefited from the recent advances. However, there is one type of neural networks, which has earned truly massive amounts of hype (in my humble opinion definitely for a reason)- Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). I can agree that those models are fascinating and I am always on a lookout for some new GAN ideas.

Inspired by this very modest reddit discussion, I have decided to make a quick overview of the most interesting publications from 2018 regarding GANs. The list is highly subjective - I have chosen research papers which were not only state-of-the-art, but also cool and highly enjoyable. In this first chapter I will discuss three publications. By the way, if you are interested in older GAN papers, this article may be helpful. One of the papers mentioned by the author even made it to my top list.

- GAN Dissection: Visualizing and Understanding Generative Adversarial Networks - given the amount of hype around GANs, it is obvious that this technology, sooner or later, would be used commercially. However, because we know so little about their inner mechanism, I think that it remains difficult to create a reliable product. This work takes a huge leap towards the future, where we are able to truly control GANs. Definitely check out their great interactive demo, the results are stunning!

- A Style-Based Generator Architecture for Generative Adversarial Networks - NVIDIA research team regularly comes up with trail-blazing concepts (great image inpainting paper from 2018, quite recent demo of using neural networks for graphics rendering). This paper is no exception, plus the video which shows their results is simply mesmerising.

- Evolutionary Generative Adversarial Networks - this is a really readable and simply clever publication. Evolutionary algorithms together with GAN - this is bound to be cool.

GAN Dissection: Visualizing and Understanding Generative Adversarial Networks

Details

The paper has been submitted on 26.11.2018. The authors have created a great project website with interactive demo.

Main idea:

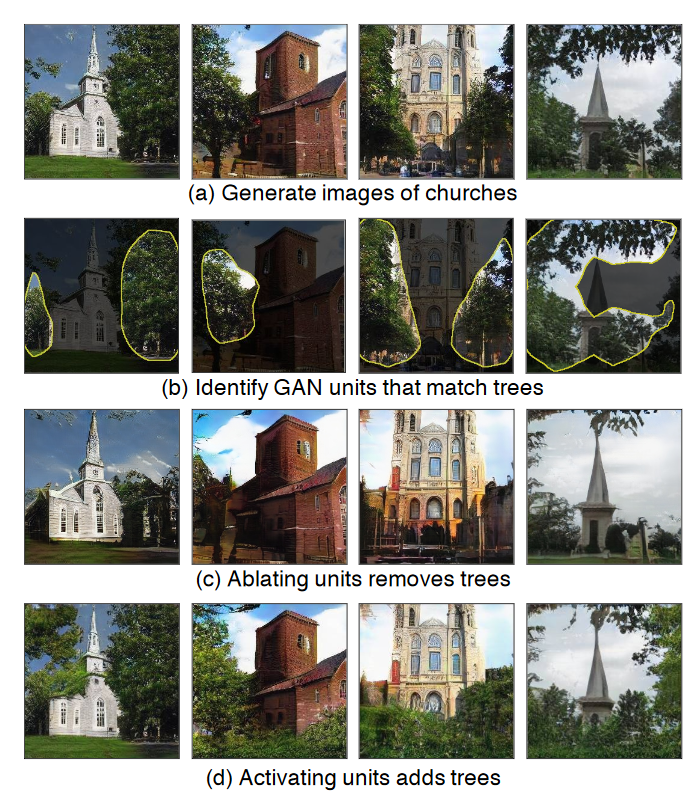

GANs have undoubtedly proven how powerful the deep neural networks are. There is something beautiful about the way a machine learns to generate stunning, high resolution images as if it understood the world like we do. But, just like the rest of those wonderful statistical models, their biggest flaw is the lack of interpretability. This research makes a very important step towards understanding GANs. It allows us to find units in the generator that a “responsible” for generation of certain objects, which belong to some class \(c\). The authors claim, that we can inspect a layer of the generator and find a subset of it’s units which cause the generation of \(c\) objects in the generated image. The authors search for the set of “causal” units for each class by introducing two steps: dissection and intervention. Additionally, this is probably the first work, which provides systematic analysis for understanding of the GANs’ internal mechanisms.

The method:

A generator \(G\) can be viewed as a mapping from a latent vector \(\textbf{z}\) to an generated image \(\textbf{x} = G(\textbf{z})\) . Our goal is to understand the \(\textbf{r}\), an internal representation, which is an output from particular layer of the generator \(G\).

\[\textbf{x}=G(\textbf{z})=f(\textbf{r})\]We would like to inspect \(\textbf{r}\) closely, with respect to objects of the class \(c\). We know that \(\textbf{r}\) contains an encoded information about the generation of those particular objects. Our goal is to understand how is this information encoded internally. The authors claim that there is a way to extract those units from \(\textbf{r}\), which are being responsible for generation of class \(c\) objects.

\[\textbf{r}_{\mathbb{U},P} = (\textbf{r}_{U,P},\textbf{r}_{\bar{U},P})\]Here, \(\mathbb{U}=(U,\bar{U})\) is a set of all units in the particular layer, \(U\) are units of interest (causal units) and \(P\) are pixel locations. The question is, how to perform this separation? The authors propose two steps which are a tool to understand the GAN black-box. Those are dissection and intervention.

Dissection - we want to identify those interesting classes, which have an explicit representation in \(\textbf{r}\). This is done by basically comparing two images. We obtain the first image by computing \(\textbf{x}\), and then running in through a semantic segmentation network. This would return pixel locations \(\textbf{s}_{c}(\textbf{x})\) corresponding to the class of interest (e.g. trees). The second image is being generated by taking \(\textbf{r}_{u,P}\), upsampling it so it matches the dimension of \(\textbf{s}_c(\textbf{x})\) and then thresholding it to have a hard decision on which pixels are being “lit” by this particular unit. Finally we calculate spatial agreement between both outputs. The higher the value, the higher the causal effect of a unit \(u\) on a class \(c\). By performing this operation for every unit, we should eventually find out, which classes have an explicit representation in the structure of \(\textbf{r}\).

Intervention - at this point we have identified the relevant classes. Now, we attempt to find the best separation for every class. This means that on one hand we ablate (suppress) unforced units, hoping that the class of interest would disappear from the generated image. On the other hand, we amplify their influence of causal units on the generated image. This way we can learn how much they contribute to the presence of the class of interest \(c\). Finally, we segment out the class \(c\) from both images and make a comparison. The less agreement between the semantic maps, the better. This means that on one image we have completely ‘tuned out’ the influence of trees, while the second image contains solely a jungle.

Results:

The results show that we are on a good track to understand the internal concepts of a network. Those insights can help us improve the network’s behavior. Knowing which features of the image come from which part of the neural network is very valuable for interpretation, commercial use and further research.

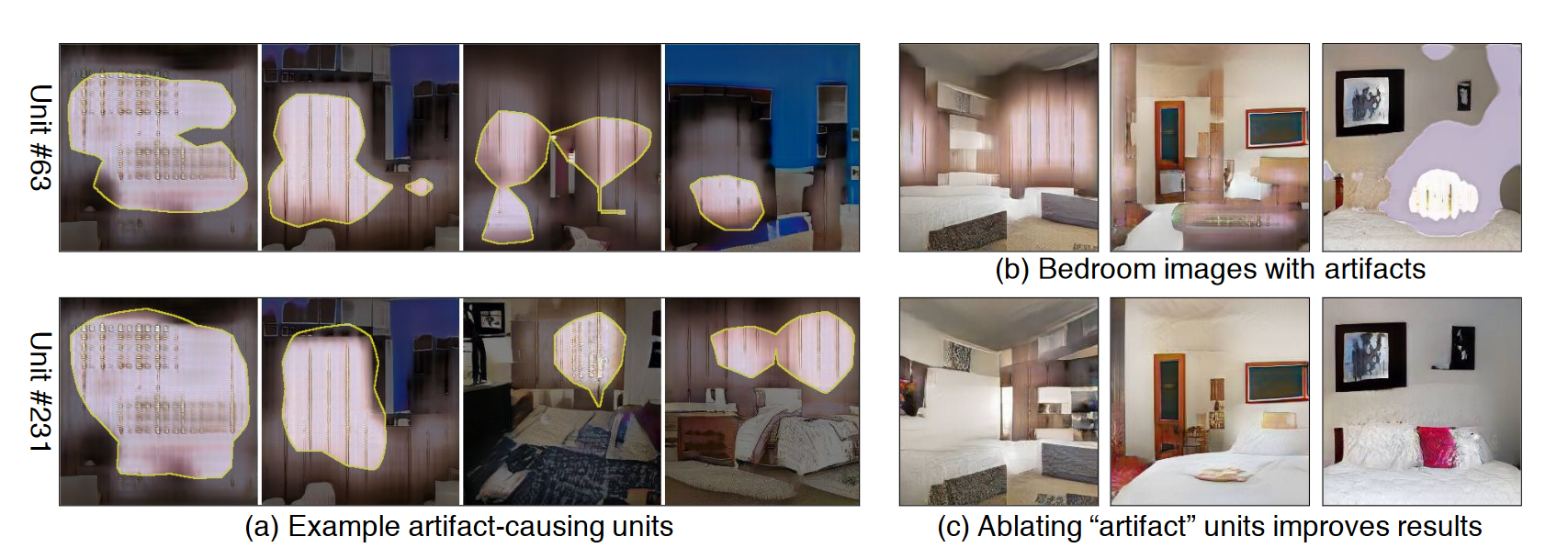

One problem which could be tackled are visual artifacts in the generated images. Even a well-trained GAN can sometimes generate a terribly unrealistic image and the causes of these mistakes have been previously unknown. Now we may relate those mistakes with sets of neurons that cause the visual artifacts. By identifying and suppressing those units, one can improve the the quality of generated images.

By setting some units to the fixed mean value e.g. for doors, we can make sure that the doors will be present somewhere in the image. Naturally, this cannot violate the learned statistics of the distribution (we cannot force doors to appear in the sky). Another limitation comes from the fact, that some objects are so inherently linked to some locations, that it is impossible to remove them from the image. As an example: one cannot simply remove chairs from a conference hall, only reduce their density or size.

A Style-Based Generator Architecture for Generative Adversarial Networks

Details

The paper has been submitted on 12.12.2018. The authors assure that the code is to be released soon. Additionally, for people who would like to read more about this method but do not want to read the paper itself, there has been a nice summary published in a form of a blog post just two days ago.

Main idea:

This work proposes an alternative view on GAN framework. More specifically, it draws inspiration from the style-transfer design to create a generator architecture, which can learn the difference between high-level attributes (such as age, identity when trained on human faces or background, camera viewpoint, style for bed images) and stochastic variation (freckles, hair details for human faces or colours, fabrics when trained on bed images) in the generated images. Not only it learns to separate those attributes automatically, but it also allows us to control the synthesis in a very intuitive manner.

The method:

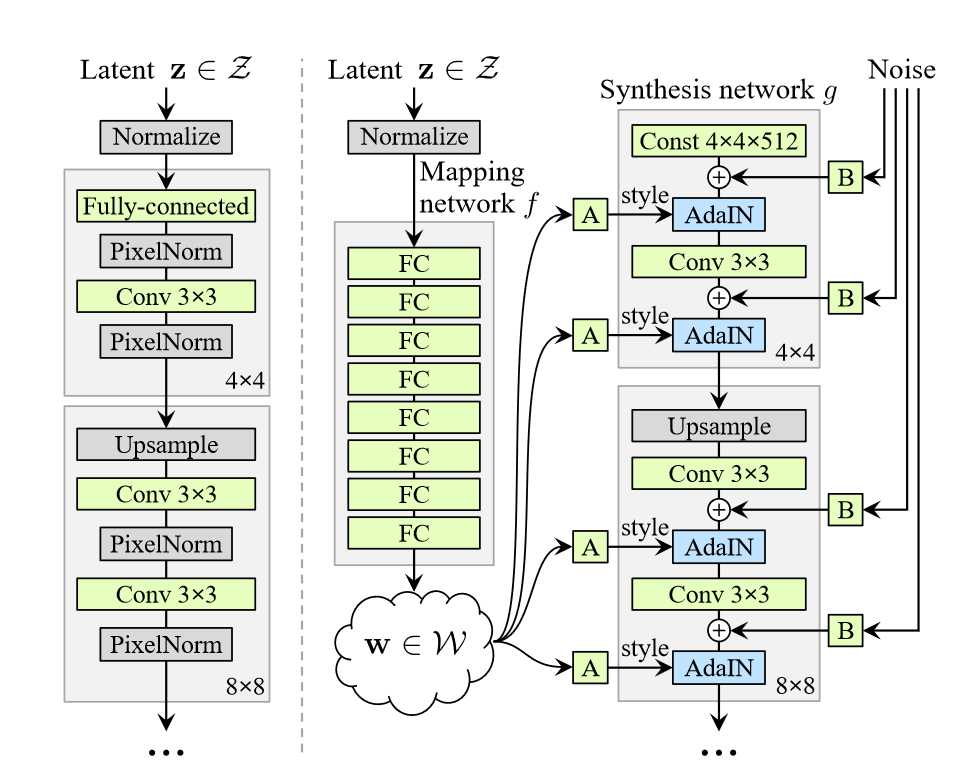

In the classical GAN approach, the generator takes some latent code as an input and outputs an image, which belongs to the distribution it has learned during the training phase. The authors depart from this design by creating a style-based generator, comprised of two elements:

- A fully connected network, which represents the non-linear mapping \(f:\mathcal{Z} \rightarrow \mathcal{W}\)

- A synthesis network \(g\).

Fully connected network - By transforming a normalized latent vector \(\textbf{z} \in \mathcal{Z}\), we obtain an intermediate latent vector \(\textbf{w} = f(\textbf{z})\). The intermediate latent space \(\mathcal{W}\) effectively controls the style of the generator. As a side note, the authors make sure to avoid sampling from areas of low density of \(\mathcal{W}\). While this may cause loss of variation in \(\textbf{w}\), it is said to ultimately result in better average image quality. Now, a latent vector \(\textbf{w}\) sampled from intermediate latent space is being fed into the block “A” (learned affine transform) and translated into a style \(\textbf{y} =(\textbf{y}_{s},\textbf{y}_{b})\). The style is finally injected into the synthesis network through adaptive instance normalization (AdaIN) at each convolution layer. The AdaIN operation is defined as:

\[AdaIN(\textbf{x}_i,\textbf{y})=\textbf{y}_{s,i}\frac{\textbf{x}_i-\mu(\textbf{x}_i)}{\sigma(\textbf{x}_i)}+\textbf{y}_{b,i}\]Synthesis network - AdaIN operation alters each feature map \(\textbf{x}_{i}\) by normalizing it, and then scaling and shifting using the components from the style \(\textbf{y}\). Finally, the feature maps of the generator are also being fed a direct means to generate stochastic details - explicit noise input - in the form of single-channel images containing uncorrelated Gaussian noise.

To sum up, while the explicit noise input may be viewed as a “seed” for the generation process in the synthesis network, the latent code sampled from \(\mathcal{W}\) attempts to inject a certain style to an image.

Results:

The authors revisit NVIDIA’s architecture from 2017 Progressive GAN. While they hold on to the majority of the architecture and hyperparameters, the generator is being “upgraded” according to the new design. The most impressive feature of the paper is style mixing.

The novel generator architecture gives the ability to inject different styles to the same image at various layers of the synthesis network. During the training, we run two latent codes \(\textbf{z}_{1}\) and \(\textbf{z}_2\) through the mapping network and receive corresponding \(\textbf{w}_1\) and \(\textbf{w}_2\) vectors. The image generated purely by \(\textbf{z}_1\) is known as the destination. It is a high-resolution generated image, practically impossible to distinguish from a real distribution. The image generated only by injecting \(\textbf{z}_2\) is being called a source. Now, during the generation of the destination image using \(\textbf{z}_1\), at some layers we may inject the \(\textbf{z}_2\) code. This action overrides a subset of styles present in the destination with those of the source. The influence of the source on the destination is controlled by the location of layers which are being “nurtured” with the latent code of the source. The lower the resolution corresponding to the particular layer, the bigger the influence of the source on the destination. This way, we can decide to what extent we want to affect the destination image:

- coarse spatial resolution (resolutions \(4^2 - 8^2\)) - high level aspects (such as hair style, glasses or age)

- middle styles resolution (resolutions\(16^2 - 32^2\)) - smaller scale facial features (hair style details, eyes)

- fine resolution resolutions (resolutions \(64^2 - 1024^2\)) - just change small details such as hair colour, tone of skin complexion or skin structure

The authors apply their method further to images of cars, bedrooms and even cats, with stunning, albeit often surprising results. I am still puzzled why a network decides to affect the positioning of paws in cat images, but does not care about rotation of wheels in car images…

Evolutionary Generative Adversarial Networks

Details

The paper has been submitted on 1.03.2018.

Main idea:

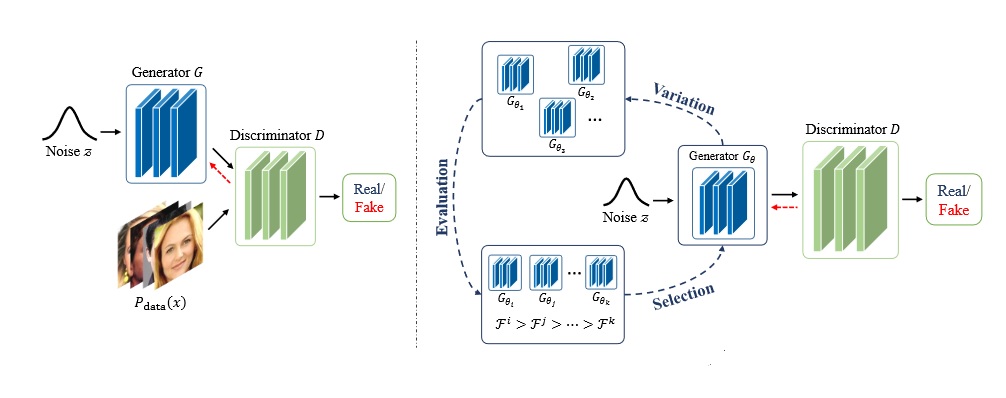

In the classical setting GANs are being trained by alternately updating a generator and discriminator using back-propagation. This two-player minmax game is being implemented by utilizing the cross-entropy mechanism in the objective function. The authors of E-GAN propose the alternative GAN framework which is based on evolutionary algorithms. They restate loss function in form of an evolutionary problem. The task of the generator is to undergo constant mutation under the influence of the discriminator. According to the principle of “survival of the fittest”, one hopes that the last generation of generators would “evolve” in such a way, that it learns the correct distribution of training samples.

The method:

An evolutionary algorithm attempts to evolve a population of generators in a given environment (here, the discriminator). Each individual from the population represents a possible solution in the parameter space of the generative network. The evolution process boils down to three steps:

- Variation: A generator individual \(G_{\theta}\) produces its children \(G_{\theta_{0}}, G_{\theta_{1}}, G_{\theta_{2}}, ...\) by modifying itself according to some mutation properties.

- Evaluation: Each child is being evaluated using a fitness function, which depends on the current state of the discriminator

- Selection: We assess each child and decide if it did good enough in terms of the fitness function. If yes, it is being kept, otherwise we discard it.

Those steps involve two concepts which should be discussed in more detail: mutations and a fitness function.

Mutations - those are the changes introduced to the children in the variation step. There are inspired by original GAN training objectives. The authors have distinguished three, the most effective, types of mutations. Those are minmax mutation (which encourages minimization of Jensen-Shannon divergence), heuristic mutation (which adds inverted Kullback-Leibler divergence term) and least-squares mutation (inspired by LSGAN).

Fitness function - in evolutionary algorithm a fitness function tells us how close a given child is to achieving the set aim. Here, the fitness function consists of two elements: quality fitness score and diversity fitness score. The former makes sure, that generator comes up with outputs which can fool the discriminator, while the latter pays attention to the diversity of generated samples. So one hand, the offsprings are being taught not only to approximate the original distribution well, but also to remain diverse and avoid the mode collapse trap.

The authors claim that their approach tackles multiple, well-known problems. E-GANs not only do better in terms of stability and suppressing mode collapse, it also alleviates the burden of careful choice of hyperparameters and architecture (critical for the convergence). Finally, the authors claim the E-GAN converges faster that the conventional GAN framework.

Results:

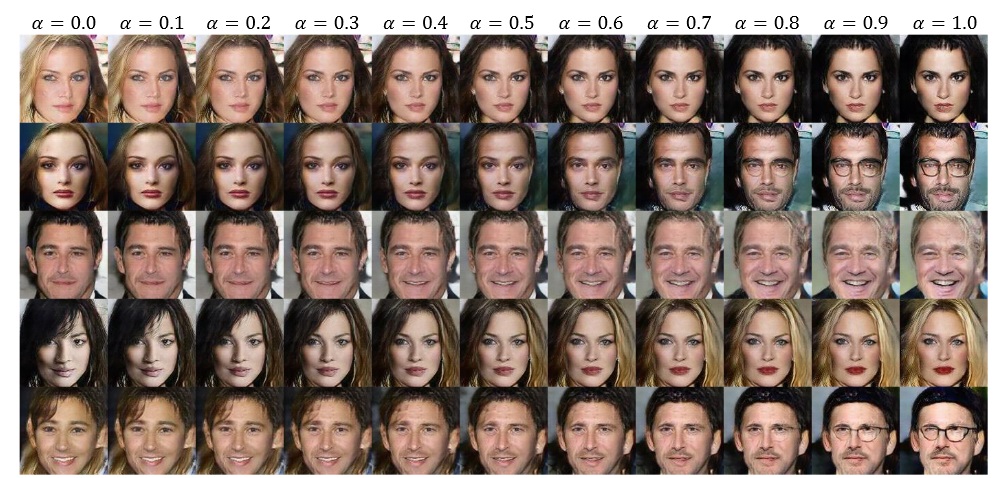

The algorithm has been tested not only on synthetic data, but also against CIFAR-10 dataset and Inception score. The authors have modified the popular GAN methods such as DCGAN and tested them on real-life datasets. The results indicate, that E-GAN can be trained to generate diverse, high-quality images from the target data distribution. According to the authors, it is enough to preserve only one child in every selection step to successfully traverse the parameter space towards the optimal solution. I find this property of E-GAN really interesting. Moreover, by scrutinizing the space continuity, we can discover, that E-GAN has indeed learned a meaningful projection from latent noisy space to image space. By interpolating between latent vectors we can obtain generated images which smoothly change semantically meaningful face attributes.

The generator has learned distribution of images from CelebA dataset. \(\alpha = 0.0\) corresponds to generating an image from vector \(\textbf{z}_1\), while \(\alpha = 1.0\) means that the image came from vector \(\textbf{z}_2\). By altering alpha, we can interpolate in latent space with excellent results.

All the figures are taken from the publications, which are being discussed in my blog post